Jan Heweliusz – astronomer, inventor and brewer from Gdańsk

- Damian Brzeski

- Sep 16, 2025

- 15 min read

Updated: Dec 15, 2025

It is not without reason that Jan Heweliusz is considered the most outstanding citizen of Gdańsk in history – his name has been inflected in every case for centuries and is present in every space of the city.

A brewer who financed his own observatory, an astronomer who was the first to map the Moon in detail, and an inventor whose genius was admired by royal courts.

Discover how a Gdańsk native left his mark on science and culture, and his legacy continues to shine like the stars he studied.

Jan Heweliusz – Gdańsk astronomer, inventor and brewer

Imagine 17th-century Gdańsk – the vibrant, wealthy heart of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and one of the most important port cities in Europe.

Amid the bustle of merchants, the aroma of spices and freshly brewed beer, lived a man who combined the earthly with the heavenly with extraordinary ease.

His name was Jan Heweliusz . He was not only an astronomer who was the first to map the lunar surface, but also a respected brewer, an influential city councilor, and a brilliant inventor.

His story is not just the biography of a great scientist. It's the story of how a great mind, fueled by the income from the famous Gdańsk brewery, could literally reach for the stars.

This is the story of a man whose genius was inextricably intertwined with his identity – a proud resident of Gdańsk, a true Renaissance man who can sometimes be boldly called the “Polish da Vinci.”

I invite you on a journey in the footsteps of Jan Heweliusz from Gdańsk to discover how the worlds of science, business and politics could meet in one person, creating an absolutely unique figure.

The life and work of Jan Hevelius

Before Jan Hevelius became one of the leading scientists in Europe, his fate was shaped by his family, his city, and his outstanding teachers.

This part of his biography traces his journey from a wealthy brewer's son to a renowned member of the international "republic of scholars," showing how solid foundations and key encounters shaped his scientific future.

Youth and education in Gdańsk

The groundwork for Hevelius's future great achievements was laid very early. He was born on January 28, 1611, in Gdańsk, into a wealthy and respected family of Lutheran brewers, the son of Abraham and Kordula, née Hecker.

The financial independence provided by the family business was the cornerstone on which he could build his scientific passion.

His formal education began at the parish school at St. John's Church, the same church where he was baptized.

He then entered the prestigious Academic Gymnasium, where his extraordinary talent was quickly recognized. Interestingly, his studies were interrupted by the plague raging in the city.

Jan Heweliusz took advantage of this unexpected turn of events in an unusual way – he set off for Pomerania to learn the Polish language, which proves his deep roots in the culture of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth.

At the age of 19, in accordance with the wishes of his father, who envisioned him as a successor in the family business, Jan set off to college. However, astronomy was not his official field of study.

In 1630, he began studying law and economics at the renowned University of Leiden . After completing his studies, from 1631 to 1634, he traveled across Europe, visiting England and France. However, this was no typical tourist escapade.

Hevelius actively sought contacts in the world of science, meeting the leading minds of the era, such as Pierre Gassendi and Marin Mersenne.

This journey allowed him to build an invaluable network of correspondents , which he maintained throughout his life, becoming a key link in the European "republic of scholars."

The role of Piotr Krüger in the development of the passion for astronomy

Every great mind needs a spark to ignite a fire within. For the young Johannes Hevelius, that spark was Piotr Krüger – an eminent mathematician, astronomer, and professor at the Academic Gymnasium. Krüger was much more than a teacher.

He became a mentor who saw extraordinary potential in his student and introduced him not only to the theoretical mysteries of astronomy, but also to its practical aspects.

It was under his supervision that Hevelius learned the art of constructing precision instruments and engraving – skills crucial for a future astronomer.

This master-disciple relationship had its climax and an extremely moving moment.

In 1639, on his deathbed, Krüger summoned Hevelius and asked him to make a promise : that his most talented student would not abandon astronomy for business and municipal affairs, but would devote his life to it.

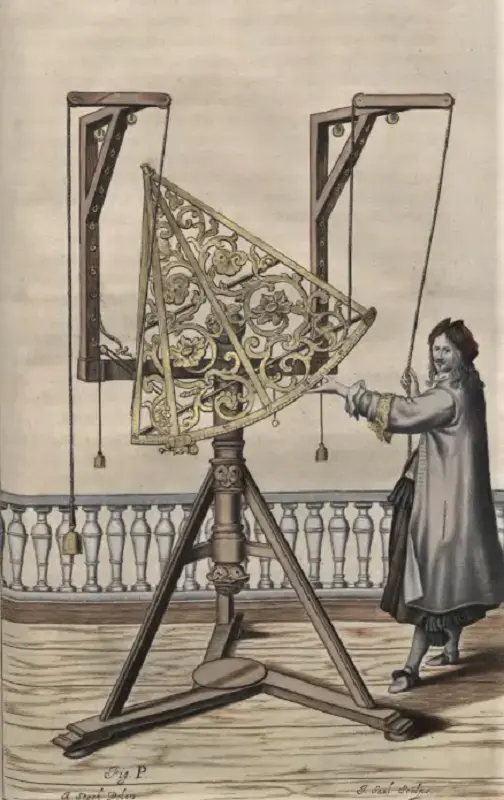

His mentor's last will became a moral imperative for Hevelius , transforming his youthful fascination into a lifelong mission. The fact that Krüger left him an unfinished azimuthal quadrant, which he later completed on his own, takes on a symbolic meaning.

It was like passing the baton in a relay race of generations of Gdańsk astronomers.

Marriages and Family Life: Katarzyna Rebeschke and Elżbieta Koopman Heweliusz

Hevelius's personal life was as fascinating as his work, and the two women he married played crucial, though completely different, roles in his success.

One could say that his marriages symbolized the two pillars on which his life rested: a solid, earthly foundation and lofty, intellectual aspirations.

His first wife, Katarzyna Rebeschke , married in 1635, proved to be an invaluable business partner. She took over most of the responsibilities associated with running the family breweries, freeing Jan's time and energy to pursue his passion for astronomy.

Moreover, Catherine brought two neighboring tenement houses as her dowry, which, when connected to Hevelius's house, created a space on whose roofs he could build his famous observatory.

Her pragmatism provided the material basis for his scientific dreams.

A year after Catherine's death, in 1663, Hevelius married Elizabeth Koopman , who was only 16 years old. This marriage proved to be a turning point.

Elżbieta, unlike her predecessor, was not interested in running a brewery – she was fascinated by astronomy.

She quickly became not only her wife but also her husband's closest scientific collaborator. She actively participated in nighttime observations, assisted in operating the complex instruments, and corresponded with European scientists.

Her role became absolutely invaluable after Hevelius's death in 1687. It was Elizabeth who undertook the titanic task of completing and publishing her husband's life's work – the great star catalog Prodromus astronomiae .

Thanks to her determination and the financial support of King Jan III Sobieski, Hevelius's scientific work was not wasted.

In 1690, she published this monumental work, accompanying it with a magnificent celestial atlas , Firmamentum Sobiescianum . She proudly signed the dedication to the king: "Elisabeth, widow of Hevelius," permanently etching her place in history as one of the most important female astronomers in history.

Membership of the Royal Society and contacts with European scientists

The fame of the Gdańsk astronomer quickly crossed the borders of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth.

Proof of his international recognition was his admission on March 30, 1664, as a member of the Royal Society of London, one of the most prestigious scientific institutions in the world.

It was a great honour, which officially confirmed that Gdańsk, thanks to Hevelius , had become one of the key scientific centres of Europe.

His membership was not merely a formality. Hevelius actively participated in the international exchange of ideas. The Royal Society's archives and Johannes Hevelius's surviving correspondence testify to his lively contacts with the most important figures of his era.

He shared his discoveries and wasn't afraid to engage in scientific debates. This network of contacts was invaluable to him—it provided access to the latest ideas, but at the same time exposed his work to the harsh scrutiny of the international community.

Jan Hevelius Observatory in Gdańsk

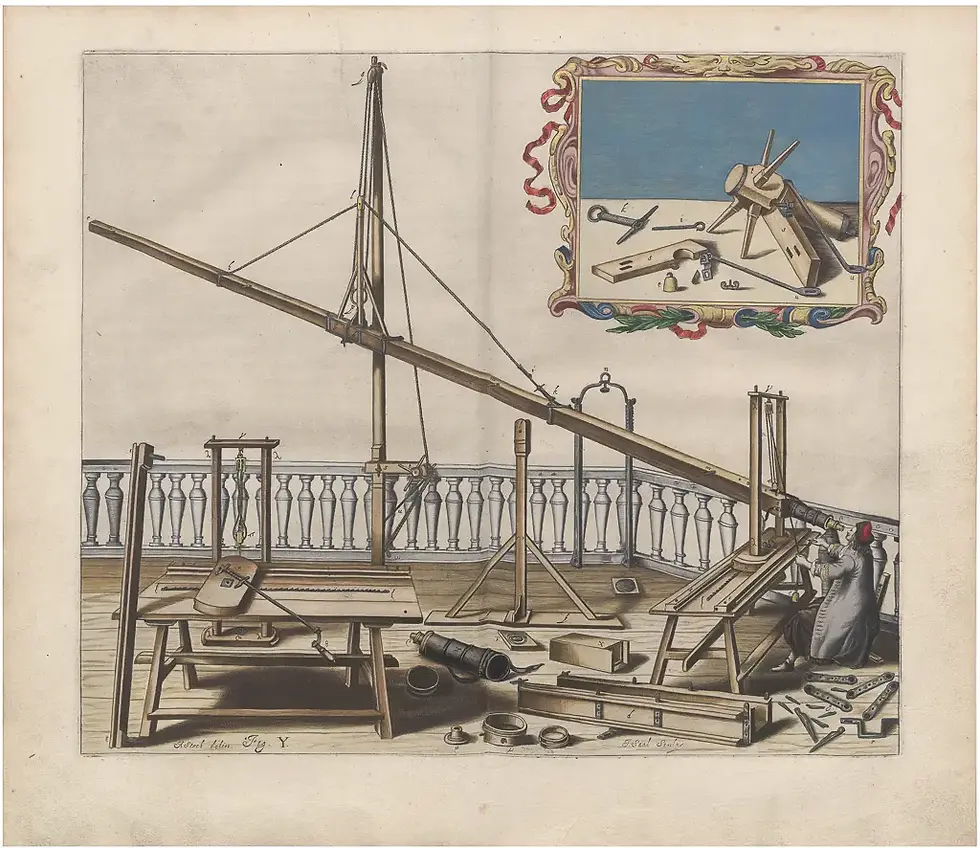

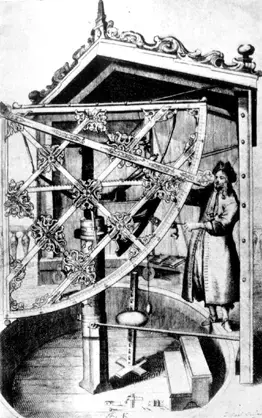

The heart of the outstanding astronomer's scientific activity was an absolutely unique place – a marvel of 17th-century engineering built on the roofs of Gdańsk tenement houses.

It was here, at Hevelius's astronomical observatory , that he made his greatest discoveries. Let's learn about its construction, equipment, and the dramatic fate that befell this extraordinary research center.

Location and construction of the observatory on Korzenna Street

The heart of Hevelius's scientific endeavors was his extraordinary astronomical observatory, which he proudly named Stellaeburgum , or "Star Castle." It was a true marvel of 17th-century engineering.

The Jan Hevelius Observatory was built in 1641 on a huge platform that stretched across the connected roofs of his three tenement houses on Korzenna Street.

This location was incredibly symbolic – his scientific endeavor literally grew out of the foundations of his commercial success.

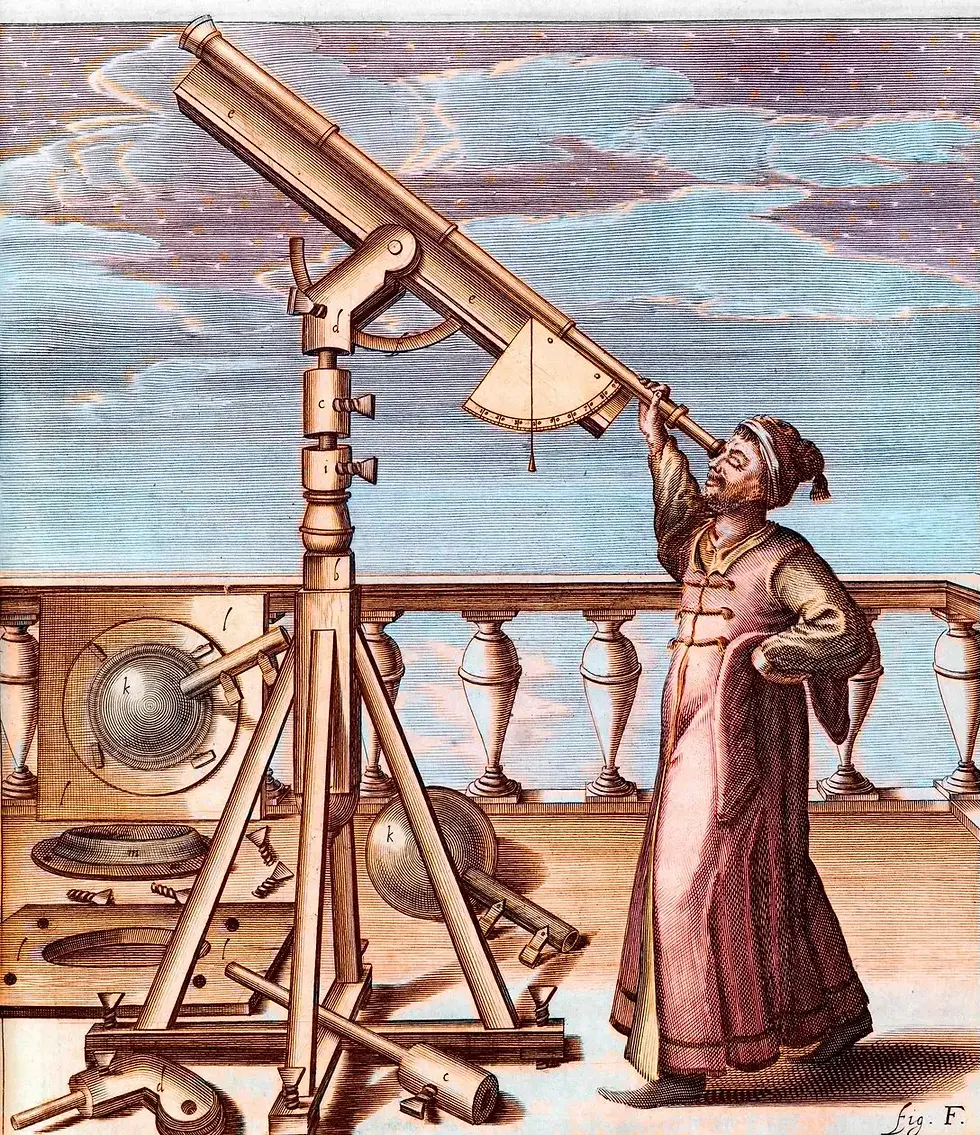

This was no ordinary platform. Hevelius created a fully self-sufficient research institute, complete with rotating pavilions, a workshop, and even his own printing house. He designed and manufactured most of the instruments himself.

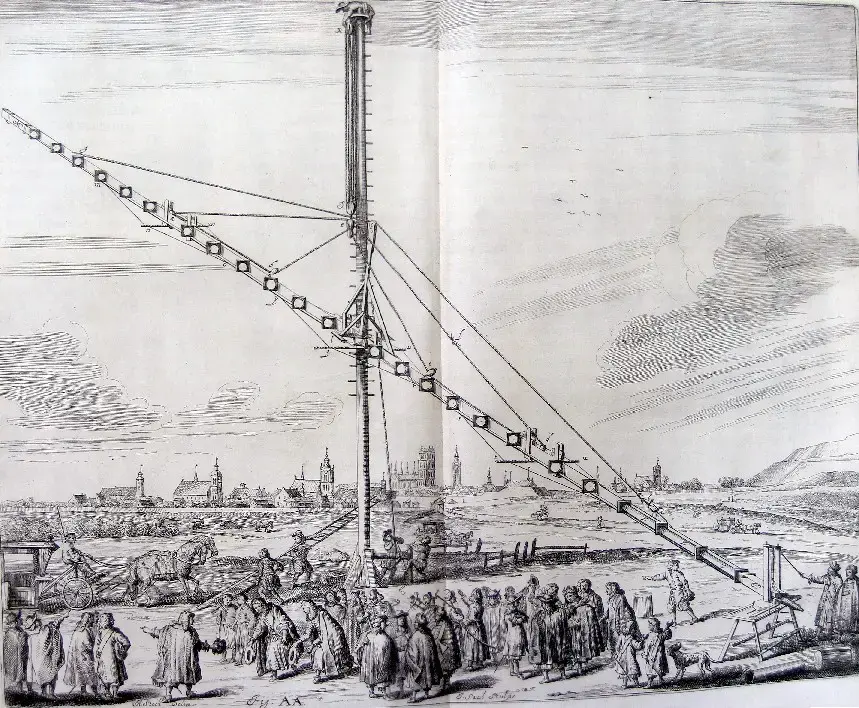

His pride and joy were his powerful telescopes, the largest of which, with a focal length of 50 meters, was the longest telescope of its time . Its tube was so enormous that Hevelius had to mount it on a special mast outside the city walls, and its operation was a public spectacle.

Unfortunately, this magnificent place met a tragic end. On the night of September 26-27, 1679, a fire broke out, completely destroying the "Star Castle."

Despite this, the Gdańsk native didn't give up. With the support of his friends and King John III Sobieski, he quickly rebuilt the Hevelius Observatory . In memory of the lost instruments, he named one of the newly discovered constellations Sextans .

Edmond Halley's visit and confirmation of the precision of the measurements

In the second half of the 17th century, a dispute raged in European astronomy: the traditional mastery of the human eye versus the new technology.

On one side stood Jan Heweliusz , trusting in the precision of his instruments with open sights.

On the other hand, in London, the influential Robert Hooke, who claimed that the Gdańsk native's observations were worthless without telescopic sights.

To finally settle the dispute, the Royal Society sent its emissary to Gdańsk – a young and extremely talented astronomer, 23-year-old Edmond Halley (who was later to discover the famous comet).

In May 1679, the two scientists conducted parallel observations of the sky for two months. Halley used modern instruments with telescopes, while Hevelius used his traditional ones.

Halley's verdict was a shock to skeptics, and a great triumph for Hevelius . The young Englishman marveled at the fact that the Gdańsk scientist's measurements, made with the naked eye, were as precise as those obtained with the latest telescopes .

Halley's visit not only confirmed Hevelius's mastery – in this way, Johannes Hevelius proved that in science it is not only technology that counts, but above all the artistry, patience and genius of the observer.

Hevelius's most important scientific works

The Gdańsk astronomer Jan Heweliusz left behind a legacy that will forever be etched in the history of science. His richly illustrated books, printed in his own publishing house, were not only a testament to his genius but also an editorial masterpiece.

Below we present the most important works of Jan Hevelius , which revolutionized the perception of the Moon, comets and star maps.

Title | Year of publication | Meaning |

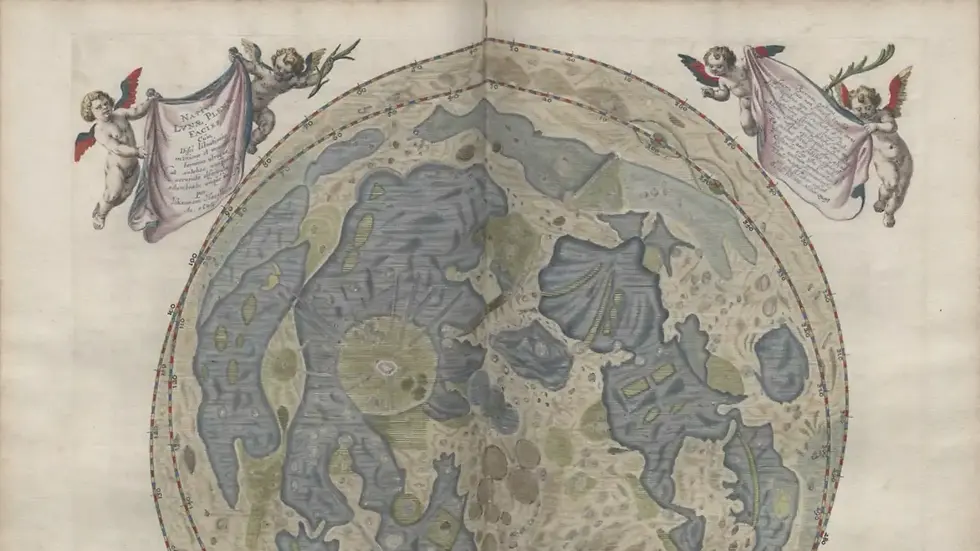

Selenographia, sive Lunae descriptio | 1647 | The first-ever detailed lunar atlas. It established Hevelius as the "creator of lunar topography." It included a description of the phenomenon of libration. |

Cometographia | 1668 | A catalog of comets, in which he presented the revolutionary thesis that comets move around the Sun in parabolic paths. |

Machinae coelestis | 1673 (part 1), 1679 (part 2) | A monumental description of his observatory and research methods. A key argument in the dispute over the precision of his measurements. |

Prodromus astronomiae & Firmamentum Sobiescianum | 1690 (posthumously) | A lifetime's work, it included a catalog of 1,564 stars and a magnificent sky atlas. It introduced seven new constellations. |

Selenographia – the first maps of the Moon

Published in 1647, Selenographia was the work that brought Hevelius European fame.

This was the first true lunar atlas in history, and its maps remained unsurpassed for over a century. In this work, he was the first to describe and explain the phenomenon of libration—the subtle "wobble" of the Moon.

Cometographia – a catalog of comets and their trajectories

In Cometographia from 1668, Hevelius collected knowledge about all known comets, adding descriptions of four of his own discoveries.

His most important contribution, however, was the revolutionary hypothesis that comets move in parabolic paths around the Sun. This was a quantum leap in understanding the dynamics of the Solar System.

Machinae coelestis – description of instruments and observation methods

This two-volume work, Machinae coelestis , was Hevelius's methodological manifesto.

In the face of criticism from Robert Hooke, the Gdańsk astronomer described his instruments and observational techniques in great detail, defending his scientific integrity.

The tragic fire of 1679 destroyed almost the entire edition of the second part, making the surviving copies priceless rarities.

Prodromus astronomiae – star catalog and sky atlas

Published posthumously by Elizabeth, Prodromus astronomiae was the culmination of Hevelius's entire life. This monumental work included a precise catalog of the positions of 1,564 stars and a magnificent sky atlas titled Firmamentum Sobiescianum .

It was one of the most important star catalogues of the pre-telescopic era, and the Johannes Hevelius prodromus project became the foundation for future generations of astronomers.

Atlas of celestial bodies and new constellations, including the Sobieski Shield

Johannes Hevelius not only measured the positions of stars but also reorganized the sky map. He introduced more than a dozen new constellations to astronomy, seven of which are still used today: Canes, Lynx, Lizard, Fox, Leo Minor, Sextant, and Scutum.

The latter has a special history. Hevelius named it Scutum Sobiescianum (Sobieski's Shield) in honor of his most important patron, King John III Sobieski. It was a brilliant act of gratitude.

Instead of giving his patron a perishable gift, the renowned astronomer placed his coat of arms on an eternal map of the sky, guaranteeing him immortality among the stars.

Inventions and contributions to the development of science

Hevelius's genius was not limited solely to stargazing. He was also a prolific inventor and meticulous researcher whose interests ranged from optics to solar physics.

This section sheds light on lesser-known but equally fascinating aspects of Hevelius's scientific activity .

Polemoscope – periscope prototype

One of Hevelius's most interesting inventions was the polemoscope – an optical device considered the prototype of the modern periscope.

It allowed for observation of the surroundings from a hidden perspective. King Jan III Sobieski was so fascinated by its military potential that he commissioned several copies from Heweliusz .

Observations of sunspots and faculae

Hevelius was one of the pioneers of systematic solar observations. He conducted detailed studies of sunspots and introduced the term faculae (Latin for "little torches") to astronomy to describe the brighter areas visible on the solar surface. This term is still used by astrophysicists today.

Maunder Minimum Documentation

Perhaps Hevelius's greatest, though unintentional, contribution to modern science is his notes on solar activity.

His main observation period almost perfectly coincides with the so-called Maunder Minimum —a puzzling period when almost no sunspots appeared on the Sun, coinciding with the coldest phase of the Little Ice Age. Hevelius diligently recorded what he saw—usually, the absence of sunspots.

Today, as climatologists study the relationship between solar activity and Earth's climate, precise records are worth their weight in gold.

Patrons and support for scientific activities

Conducting such advanced and expensive research required enormous financial resources.

Although the basis was income from breweries, the support of powerful patrons was crucial, and Johannes Hevelius was able to secure it by gaining the patronage of the two most powerful monarchs of Europe at that time.

Jan III Sobieski – royal protector of science

Hevelius's relationship with King Jan III Sobieski went far beyond the standard patron-artist relationship. The king was genuinely fascinated by astronomy.

King Sobieski granted the scientist a fixed annual salary , exempted his breweries from taxes, and after the tragic fire, he was one of the first to provide financial assistance for the reconstruction of the Jan Hevelius observatory .

Louis XIV – French patronage and salary for an astronomer

Hevelius's fame also reached the court of the Sun King, Louis XIV . The French ruler, striving to make Paris the scientific capital of Europe, awarded the Gdańsk native an annual pension, which he received for nine years.

As a token of gratitude, Hevelius dedicated two of his most important works to him: Cometographia and the first part of Machinae coelestis .

Having the patronage of two powerful, rival monarchs was a diplomatic masterpiece.

Brewery and brewing in the life of Hevelius

To fully understand Hevelius's phenomenon, we must descend from his skyward observatory to the bustling streets of Gdańsk. It is there, in the haze of malt and hops, that lies the source of his scientific power – the profitable business that financed his passion for the stars.

Jopejski beer and the tradition of Gdańsk brewing

Heweliusz was a master of producing one of the most famous export products of old Gdańsk – Jopenbier .

It was an exceptional beverage: thick, dark, and incredibly strong, considered the "king of European barley beers." It was the profits from its sale that provided the main financial engine that fueled Hevelius's passion for astronomy. Without the brewery, there would be no observatory. Without Jopean beer, there would be no maps of the Moon.

Today, you can try Jopejski beer, once brewed by Heweliusz, at the PG4 restaurant at the Central Hotel, right next to the main train station in Gdańsk.

Jan Heweliusz's Brewery as a source of income and scientific base

The physical connection between his two worlds was almost literal. The tenement houses on Korzenna Street housed bustling breweries on their ground floors, and on their roofs stood the most modern Hevelius astronomical observatory in Europe.

This extraordinary symbiosis is a perfect metaphor for Hevelius's life. He was a man who invested the wealth he acquired on earth in discovering the secrets of heaven.

Not everyone remembers, but until recently, beer was brewed in Wrzeszcz under the Hevelius brand, alongside the famous 10.5 and lesser-known brands like Artus and Gdański . The brewery in Wrzeszcz is no more – a housing estate now stands there, but in its heart lies the Nowy Browar Gdański restaurant, which today nurtures the brewing tradition of this place.

The legacy and commemoration of Jan Hevelius

The legacy of this great Gdańsk native lives on, both in his hometown and in the world of science and culture. Institutions, ships, and even beer bear his name, upholding the memory of his versatile genius and contribution to science. Jan Heweliusz is constantly present in public spaces.

Hevelianum – a modern science centre in Gdańsk, which perfectly continues the mission of its patron: arousing curiosity about the world and popularizing science.

Portraits by Schultz and Stech – famous images of the astronomer, one of which now adorns the collections of the Gdańsk Library of the Polish Academy of Sciences, and the other, which Johannes Hevelius donated to the Royal Society, is located in the Museum of the History of Science in Oxford.

Medal of the 400th anniversary of the birth – in 2011, when the Sejm declared the Year of Jan Heweliusz, a special commemorative medal was minted to commemorate the birth of Jan Heweliusz .

Hevelius beer and the ORP Heweliusz ship – his memory lives on in the beer brand referring to his roots and in the name of the hydrographic ship of the Polish Navy, which symbolically continues his mapping work.

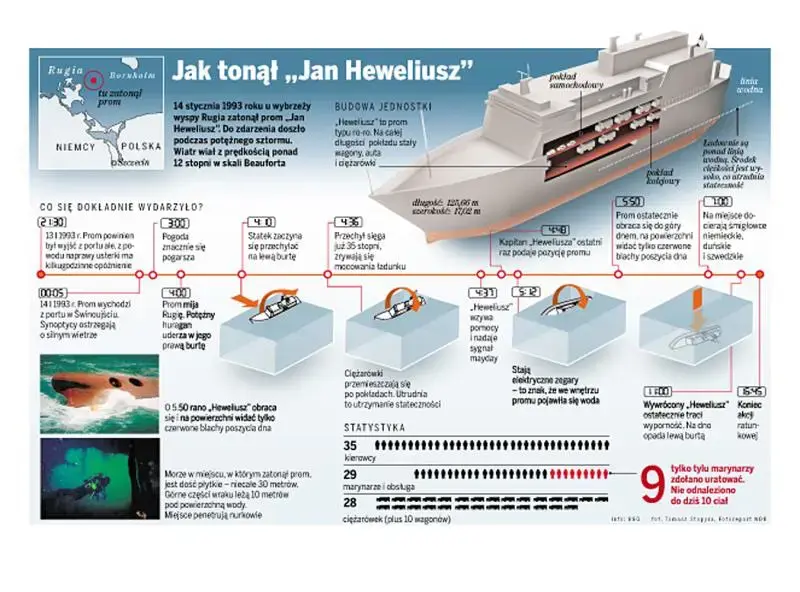

The MF Jan Heweliusz ferry and its disaster

By a tragic irony of fate, the name of a man associated with precision and the order of the sky was forever linked with one of the greatest maritime tragedies in Polish history.

This part tells the painful story of Hevelius's catastrophe , its causes and effects, which still arouse emotions today.

The history of the shuttle and its name in honor of the astronomer

The MF Jan Heweliusz rail-vehicle ferry, launched in 1977, had a bad run from the start. During its 15 years of service, it was involved in nearly 30 accidents and breakdowns.

After a serious fire, a clumsy repair was carried out, with 70 tons of concrete poured onto the deck, which had a disastrous effect on the vessel's stability. Among sailors, the ferry earned the grim nickname "the floating coffin."

The Jan Heweliusz ferry disaster of 1993 and its causes

The tragedy occurred on the night of January 14, 1993. The ferry left Świnoujście straight into a hurricane raging on the Baltic Sea.

A combination of fatal factors – extreme weather, stability problems, cargo shifting and likely crew errors – led to a violent list and sinking.

The Jan Heweliusz sank off the coast of Rügen on January 14, 1993, at 5:12 a.m. Analyzing the causes of the Heweliusz disaster , experts point to a whole chain of negligence and unfortunate coincidences.

Of the 64 people on board, 55 died . It was the worst maritime disaster in the history of the Polish peacetime merchant fleet.

The MF Jan Śniadecki ferry participated in the rescue operation

There is one touching thread in this dark story. Another Polish ferry, the MF Jan Śniadecki, interrupted its voyage to participate in the rescue operation.

It was onto this deck that helicopters transferred the bodies of victims recovered from the icy water.

Netflix's 2025 series about the ferry tragedy

The tragedy of Heweliusz and the story of Jan's catastrophe have become a permanent part of Polish consciousness, and soon the entire world will learn about them. In November 2025, the feature series "Heweliusz," directed by Jan Holoubek, will debut on Netflix.

Paradoxically, the name of the man whose life was synonymous with precision and the discovery of the laws of the cosmos will be associated with chaos, human error and tragedy on a stormy sea for millions of people around the world.

Jan Heweliusz in contemporary culture and science

Despite the tragic shadow that the disaster of Jan Hevelius cast on his name, the figure of the great astronomer remains one of the brightest symbols of Gdańsk and Polish science.

His legacy is cherished and continues to inspire, and his presence is still felt strongly in his hometown.

Hevelius Cultural Trail in Gdańsk

Walking around Gdańsk, you can literally follow in the footsteps of the great astronomer. The cultural trail leads through places key to his life: Korzenna Street,

The Old Town Hall, St. Catherine's Church, where he was buried, and his monument are just a few steps away. An additional attraction is the charming "Hewelion the Lion Trail."

Influence on the development of modern astronomy and the popularization of science

Jan Hevelius was a fundamental figure in the development of modern astronomy. His star catalogs, lunar maps, and ideas about cometary motion pushed science forward.

His seemingly prosaic notes on sunspots proved to be an invaluable source for modern climatology centuries later.

However, his greatest legacy is more universal. Jan Hevelius embodied the spirit of his city.

He was a man who proved that passion and business, community service and the pursuit of knowledge, could go hand in hand. He was a brewer who transformed the riches of the earth into tools for exploring the heavens.

Its history, like a lens, captures everything that made Gdańsk great: entrepreneurship, openness to the world, and an unwavering faith in the power of the human mind. And so, forever, the golden beer of Gdańsk merged with the silver light of the stars.

Comments